Has Musks’ America gone Ozempic crazy?

Data shows diet drugs psychiatric side effects ignored by clinical trials

We need to talk about GLP-1 agonists.

Ozempic, Mounjaro, and similar drugs are everywhere. FDA-approved for diabetes, they’re now the go-to solution for obesity, with 1 in 4 Americans planning to use them for weight loss in 2025. We’ve all heard them touted for everything from alcoholism, to polycystic ovarian syndrome.

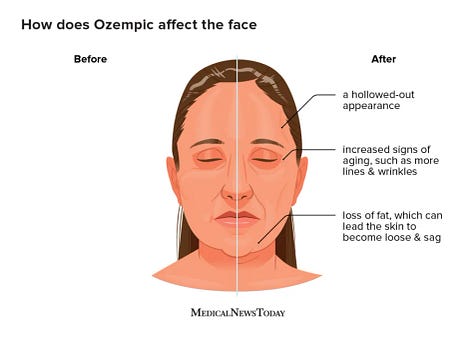

Celebrities have been quietly using them for years, and the hype is undeniable. But beneath the surface, there’s a growing unease. Terms like “Ozempic face,” “Ozempic personality,” and “Ozempic crazy” have been trending for a reason. The reality is, these drugs are not the miracle cure they’re made out to be. Recent studies, including a groundbreaking large cohort Nature publication, reveal alarming psychiatric side effects. Over an 8 year period, patients on GLP-1 agonists experienced:

Doubled suicidal ideation

Doubled anxiety

Tripled depression

To retain the weight lost on the drugs, you have to stay on them permanently. And the data shows the longer people stay on these drugs, the worse the effects become.

What went wrong?

Why weren’t these side effects flagged during clinical trials? Two reasons:

Short follow-up timeframes: Trials didn’t track long-term effects

Exclusion criteria: People with depression, anxiety, or other psychiatric conditions were excluded from the study population

This is a massive oversight. Obesity and diabetes majorly overlap with depression due to shared inflammatory biology. By excluding these populations, trials failed to capture the severe real-world risks. Case studies have associated the drugs with mania, as well as lower overall drive and motivation.

The Nature study which discovered these findings was more inclusive. However, they still excluded individuals with recent diagnoses of depression, bipolar disorder, or suicidal ideation. These are the very people most likely to be prescribed GLP-1 agonists and also the most vulnerable to their side effects.

Drugs and your brain

Just like amphetamine which was once widely prescribed for weight loss, GLP-1 agonists seem to work on the brain's reward system, but in a different manner. While amphetamines boost dopamine directly, the new drugs regulate blood sugar and appetite, indirectly influencing dopamine levels. Both can have an antidepressant effect, but here’s the behavioural link: stimulants and antidepressants (including caffeine, which is consumed daily by many) are notorious for triggering mania in genetically sensitive populations, like those with bipolar disorder.

These effects likely are apparent in a much larger group of people with sub-clinical bipolar traits or undiagnosed psychiatric disorders. It’s possible that poly-pharmacy (use of many drugs) or stacking too many interventions with similar effects (using ketamine for depression, drinking coffee, fasting, ice showers, Ozempic, to name a few), can cumulatively cause exponential increases in these symptoms.

It’s probably important to note that in the present era (neoliberal society) these traits are increasingly incentivised (obsessive productivity/grindset-hustle, attention catching behaviour, etc.) so there is also a positive feedback cycle at play in our culture increasing these traits.

Given that the drugs cause similar behavioural effects to amphetamines via different inputs to the same feedback systems, it’s no surprise they’re now being more linked in scientific literature and contemporary culture to mood swings, anxiety, and even manic behaviour in vulnerable individuals. Anyone who has ever been “hangry” is well aware of the strength of the connection between food intake and mood.

Elon’s unpleasant Musk

What are the impacts on society? A visible starting point is Elon Musk.

Musk has been vocal about his use of GLP-1 agonists like Mounjaro for years. He’s also spoken openly about his mental health struggles, including possible bipolar disorder, Aspergers and depression. Recently, his behaviour has become increasingly erratic, including (but definitely not limited to):

Manic Twitter sprees: He’s posting more than ever, often at odd hours, suggesting sleeplessness

Aggressive outbursts: His public feuds, reactive statements and controversial behaviour are escalating. As well as the scale of their impacts to society

Physical changes: Musk has lost a lot of weight and he looks gaunt, a hallmark of “Ozempic face.” He posted a picture on twitter looking skinny and calling himself “Ozempic Santa”

Then there’s Kanye West. The rap star medically diagnosed with bipolar. After dramatic weight loss, his behaviour has become more subversive and erratic, culminating in alarming public statements as well as divorce.

Coincidence? Maybe. But it’s worth asking whether these drugs are playing a role.

Societal impact

The individual risks are clear, but what about the broader implications? Celebrities are normalising these drugs, often without knowing or disclosing the risks. Meanwhile, the weight loss drug market has been booming, and is projected to grow exponentially.

But at what cost? If even a fraction of patients experience severe psychiatric side effects, we’re looking at a huge public health crisis. And when patients are powerful figures like Musk or Kanye, the huge economic and political consequences can send shockwaves through society.

How to proceed

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: although we probably should, we can’t institutionalise billionaires or celebrities, and holding them accountable through the legal system is challenging. To hold public figures accountable, direct action seems to work best. It seems to already be occurring, if Teslas collapsing share price is anything to go by. Also, see the drop in Kanyes wealth and cancelled deals.

There is a need for better education of the risks, especially for doctors and patients. And if you’re already on these drugs, monitor your mood and behaviour closely. If you are diagnosed with, or suspect you suffer from mental illness, maybe reconsider the risks of these drugs and seek professional help.

GLP-1 agonists may help some people, but they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution. And for weight loss applications, new evidence indicates the psychiatric risks may far outweigh the benefits.

Thanks for reading my first post (second version)! Subscribe for free to receive new posts. If you’re feeling overwhelmed by the scale of these problems, remember that you’re not just an isolated individual, by getting informed early and sharing quality data we can harness network effects for maximum impact! Please feel free to send me your questions and feedback, I’d highly value them :)

Reading the descriptions of how they work was enough to put me off them. Somehow the idea of keeping waste in my body for a longer period of time doesn’t appeal much to me. I think I’d rather be fat.

And I say that as someone who WAS fat all through childhood, right up until I discovered amphetamines as a teenager. In retrospect, I should have stuck with being fat.